Art & Culture

Traditional Crafts Wrapped in Stories

-

- RELATED TAGS

-

- LAST UPDATED

- 6 February, 2026

Traveling, I am often reminded that the most enduring stories are not always found in grand landmarks, but in the quiet objects that accompany everyday life. In the Setouchi region, traditional crafts have long played a role that goes beyond simple utility; they reflect human emotions, local culture, and a close relationship with the natural environment, shaped by the calm sea and the materials available in each area. Within this gentle landscape of the Seto Inland Sea, stories rooted in daily life and belief continue to be carried forward through handcrafted objects.

Setouchi has historically been a place of movement and exchange, where people, goods, and techniques traveled across the water and settled into regional forms. The crafts that developed here reflect that history. They were created for practical use, but also to express wishes for protection, prosperity, and continuity, becoming familiar presences in homes, rituals, and workspaces.

This article invites you on a journey through five traditional crafts of the Setouchi region, each carrying its own story. These are not distant traditions preserved behind glass, but living practices that welcome visitors to touch, make, and use them. By engaging directly with the people and places that sustain these crafts, it becomes easier to understand why they remain practical, meaningful, and cherished in contemporary life.

Table of Contents

- 1. Sanuki Kagari Temari, Sanuki Kagari Temari Preservation Association (Kagawa) | Colorful Balls Imbued with Prayer

- 2. Tobe Ware, En no Sato (Ehime) | From Tradition to Everyday Life: The Story of Vessels for Today

- 3. Ōtani-yaki Pottery, Yoshimi-gama Kiln (Tokushima) | Shaping the "Weight" of Fire and Clay

- 4. Tatami Edging, Takata Orimono (Okayama) | Japanese Aesthetic Sensibility Spreading from Underfoot

- 5. Ouchi Lacquerware, Nakamura Folk Crafts (Yamaguchi) | From Royal Ware to Modern Living

- 6. Summary|Traveling Through "Handicrafts"

1. Sanuki Kagari Temari, Sanuki Kagari Temari Preservation Association (Kagawa) | Colorful Balls Imbued with Prayer

Tucked away from the main road, in a former kindergarten building, I encountered Sanuki Kagari Temari, one of Kagawa’s most delicate and story-rich traditional crafts, preserved and passed down by the Sanuki Kagari Temari Preservation Association. At first glance, Temari appear as beautifully patterned balls, light enough to rest in the palm of a hand. Looking closer, each one reveals layers of careful work, patience, and meaning stitched into the surface.

Temari have a long history in Japan, dating back to the Heian period (794 - 1185). Originally made as toys for children, they gradually became objects of artistic expression, especially among court ladies, who refined their patterns using silk threads and intricate geometric designs. Over time, temari spread among common households, where they were cherished not only as toys but also as symbols of prayer. The patterns were believed to ward off evil and bring good fortune, health, and happiness.

In Kagawa, this tradition developed into Sanuki Kagari Temari, characterized by the use of locally sourced materials. The core of each ball is made from rice husks collected from nearby farmers. Threads are dyed on-site using natural methods, without chemical dyes, and stitched meticulously over the core. The process is slow and meditative, requiring intense focus.

As I learned, some patterns carry symbolic meanings. The Asanoha (hemp leaf), for example, is known for its rapid growth, so the motif has traditionally been used to wish for children's healthy growth. It is also familiar to many young people as the design on a character’s outfit in the popular anime Demon Slayer. Other motifs, such as chrysanthemums or olive-inspired designs unique to the region, reflect different wishes. Understanding these meanings adds depth to what might otherwise be seen as decorative objects.

Today, Sanuki Kagari Temari have found new roles as interior decorations and accessories, while still keeping their traditional symbolism. The preservation society, led by Eiko Araki, plays a central role in keeping the craft alive by teaching both locals and visitors. Short workshops (reservation required) allow beginners to create their own temari in just a few hours, offering a chance to engage directly with a craft that continues to connect daily life, regional identity, and quiet intention.

2. Tobe Ware, En no Sato (Ehime) | From Tradition to Everyday Life: The Story of Vessels for Today

My first encounter with Tobe-yaki happened long before I ever set foot in a pottery studio. It was a plate used to serve a dish at a restaurant in Ehime Prefecture, and later, a familiar sight at cafés and souvenir shops around Matsuyama and Dogo Onsen. Tobe-yaki has a way of blending naturally into daily life. Visiting En no Sato, one of the centers of this craft, revealed the depth behind that familiarity.

Tobe-yaki is produced primarily in Tobe Town, Ehime Prefecture, and is known for its slightly thick, white porcelain body and hand-painted designs using gosu, an indigo pigment that turns a deep blue after firing. The craft originated in the Edo period (1603-1868), when artisans began using stone dust from locally quarried grinding stones – an industry that gave the town its name. Practicality has always been central to Tobe-yaki, and its resistance to chipping and cracking has made it especially well-suited for everyday use.

At En no Sato, that philosophy carries into the visitor experience. The ground-floor shop displays a wide range of works, from classic arabesque patterns painted in flowing, calligraphic lines to contemporary designs, including cute animal motifs.

The painting workshop offers a hands-on introduction to this living tradition. After choosing a plate or small dish, I sketched my design lightly in pencil before picking up a brush. Two types were available: one wide and soft, made from white goat hair, and a finer tanuki-hair brush that demands a steadier hand. The pigments appear almost unrecognizable before firing; gosu looks nearly black until it emerges from the kiln in its signature indigo blue. As I began to paint, my hesitation quickly turned into the joy of seeing my ideas take shape. It was both a calming and exciting experience, and a chance to express my individuality within a centuries-old craft.

A few weeks later, when the finished piece arrived by post, the transformation felt complete. The bright white glaze and softened brushstrokes revealed how Tobe-yaki balances tradition with everyday practicality – an object made not just to be admired, but to be used, again and again.

3. Ōtani-yaki Pottery, Yoshimi-gama Kiln (Tokushima) | Shaping the "Weight" of Fire and Clay

The atmosphere at Yoshimi-gama Kiln is unmistakably that of a working studio. Corrugated tin, the smell of damp clay, and long tables lined with finished pieces set the scene. This is not just a display space: it is a place where pottery is actively made, and visitors are invited into that rhythm.

Ōtani-yaki has a history of more than two centuries, beginning when a potter from Kyushu demonstrated his techniques while traveling the Shikoku pilgrimage, a centuries-old route linking 88 Buddhist temples across the Shikoku Island. Ōtani developed into a kiln village known for its distinctive nerokuro, or “lying wheel.” Kicked by foot, this wheel allows potters to throw exceptionally large vessels, a technique found nowhere else in Japan. These oversized jars were historically used for storage and as vats for indigo dyeing.

The clay from the Ōtani region has a unique texture – smooth yet strong – which gives the finished pieces a natural, earthy warmth and deep color. Each kiln then brings out subtle differences in color and texture during firing. Takino Yoshihiro, a third-generation potter and longtime president of the Ōtani-yaki Pottery Association, moves through the studio with calm assurance. With more than twenty-five years at the wheel, he explains techniques mostly through gestures: where to place the thumbs, when to ease the pedal, how to respond to the clay rather than force it.

Modern Ōtani-yaki extends beyond large jars. Shelves are filled with bowls, plates, and coffee cups designed for contemporary use, many commissioned by local restaurants and cafés. Takino often adjusts shapes or glaze tones to suit a specific client. The balance is tricky: honor the rustic heart of Ōtani-yaki while shaping pieces today’s cooks and coffee-drinkers actually reach for. Despite these challenges, he gets deep satisfaction in shaping something from raw earth into a lasting form.

Visitors can choose wheel-throwing, hand-building, or painting experiences. The contrast between the expert demonstration and the physical challenge of shaping clay is immediate. Finished pieces are fired and shipped later, including overseas. What stays with me most, however, is the sense of dialogue – between soil, fire, and human hands – that defines Ōtani-yaki as a craft rooted firmly in both tradition and the present.

4. Tatami Edging, Takata Orimono (Okayama) | Japanese Aesthetic Sensibility Spreading from Underfoot

Tatami are so closely associated with Japanese interiors that it is easy to overlook the craftsmanship in their details. One of those details is tatamiberi, the decorative fabric edging that frames each tatami mat. At Takata Orimono in Okayama Prefecture, I had the opportunity to see how this quietly essential craft is made, and how it continues to adapt to changing lifestyles.

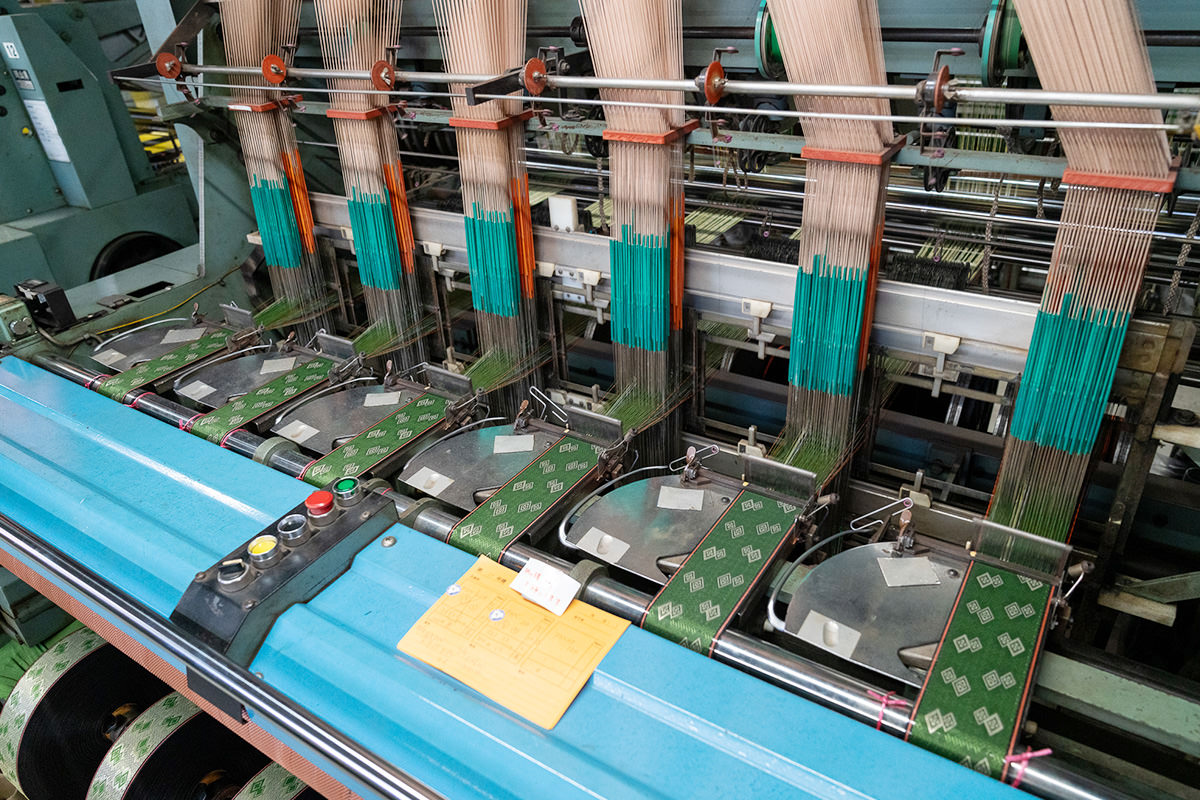

Takata Orimono specializes in producing tatami edging using a combination of modern equipment and older weaving machines. Walking through the factory, the steady rhythm of looms fills the space, weaving patterns that range from traditional geometric motifs to fun, contemporary designs. As tatami use has declined in many modern homes, the company has responded by reimagining these materials for new purposes, transforming them into bags, pouches, watch straps, and other everyday items.

Beyond technique, the visit highlighted the meaning of the word en (縁), which can refer to both an edge and a connection. Tatami edging serves as a physical border, but it also symbolizes the connections between spaces, people, and daily life. Through its products, Takata Orimono conveys the precious value of this craftsmanship, which plays a central role although it often remains hidden.

5. Ouchi Lacquerware, Nakamura Folk Crafts (Yamaguchi) | From Royal Ware to Modern Living

Ouchi lacquerware traces its origins to the cultural ambitions of the Ōuchi clan, who ruled parts of present-day Yamaguchi during the Kamakura period (1185 - 1333) and admired the refined aesthetics of Kyoto. The lacquerware developed under their patronage became a legacy that continues today in a distinctive style known as Ouchi-nuri. Visiting Nakamura Folk Crafts offers a glimpse into how this tradition has been preserved and reinterpreted across generations.

Founded in 1926 by Osamu Nakamura, the workshop has remained family-run for nearly a century. Now led by third-generation president Kou Nakamura, the production is carried out entirely in-house, from shaping wooden bases to applying layers of vermilion lacquer and finishing with maki-e decoration. The deep red surface known as Ouchi-shu is paired with gold-leaf motifs such as the diamond-shaped Ouchi-bishi crest and seasonal designs inspired by nature, all rooted in the aesthetics of the Ōuchi clan.

Alongside trays, bowls, and traditional Ouchi dolls, the shop displays newer designs that reflect contemporary tastes. Minimalist sake cups, accessories, and even playful figures inspired by pop culture sit beside classic pieces. The cheerful Rie Nakamura herself wears small smiling doll earrings, her favourite design. Not many craft people remain in the area, so keeping the tradition alive is one of the most important things.

Nakamura Folk Crafts offers studio tours, where visitors can also learn about the lacquer process and its spiritual significance (English pamphlets available), and simple hands-on experiences (prior consultation required). Their workshops invite visitors to engage directly with the craft.

Short sessions allow participants to decorate small accessories using fast-drying substitute lacquer and gold leaf, with finished items ready to take home. More traditional chopstick-making experiences are also available, requiring longer times. Through these activities, Nakamura Folk Crafts presents Ouchi lacquerware not only as a historic art form, but as a living practice that continues to connect craftsmanship, belief, and daily use.

6. Summary|Traveling Through "Handicrafts"

The Setouchi region has long developed as a maritime crossroads where people, goods, and ideas moved freely between islands and coastal towns. Within this environment, traditional crafts emerged not as isolated art forms, but as practical responses to daily life, shaped by local resources, beliefs, and the rhythms of work and ritual.

Across the five crafts explored in this journey, a common thread becomes clear. Sanuki Kagari Temari carry prayers and wishes stitched into their patterns. Tobe-yaki and Ōtani-yaki pottery translate regional materials and techniques into items meant for everyday use. Tatami edging reflects a traditional aesthetic sensibility that has evolved to meet the needs of a new era with fewer tatami-covered homes, while Ouchi lacquerware connects history with contemporary living. Each craft acts as a vessel for stories gathered through generations.

What makes the Setouchi region especially compelling is that these traditions remain accessible today. They can be visited, learned from, and experienced firsthand, offering meaningful encounters beyond typical sightseeing. By engaging directly with these crafts – touching materials, shaping forms, and understanding the intentions behind them – travelers gain a deeper appreciation of the region’s culture, making it a truly special Japanese experience.

RELATED DESTINATION

Kagawa

This is an area with many islands, including Naoshima and Teshima, which are famous for art. It also is home to the tasteful Ritsurin Garden. Kagawa is also famous for its Sanuki udon, which is so famous it attracts tourists from throughout Japan. The prefecture is even sometimes referred to as “Udon Prefecture.” [Photo : “Red Pumpkin” ©Yayoi Kusama,2006 Naoshima Miyanoura Port Square | Photographer: Daisuke Aochi]